© ????????? ??????????—?????

Alas, poor Rafal. We hardly knew you. Now, it’s Oczy’s turn in the spotlight, although he’d sooner shrink from that attention than have a single hair illuminated by it. He’s a much different protagonist, to put it lightly. Rafal was a privileged prodigy, a smarmy realist, and an inquisitive lad who eventually found his convictions and paid their price. Oczy, on the other hand, is a gloomy sword for hire who fears both God and the afterlife in equal measure, yet he finds no solace in his material existence either. These boys have almost nothing in common. What, then, is our continuity? Why would Orb take such a severe swerve?

Plotwise, the connective tissue is already evident. Last week’s preview and this week’s final scene set up Oczy and Gras’ encounter with Rafal’s secret star charts. Thematically (and more importantly), however, I’d say the stark difference between Rafal and Oczy is the point. We already know the story of people like Rafal. Under different circumstances, he would have grown up into a figure like Copernicus who would have helped advance heliocentrism into the annals of science. Oczy, a pessimistic commoner with minimal science education, is a more unlikely—and thus more interesting—hero to usher in the next leg of Orb.

Given that this is essentially a new story with a new cast (not counting a more heavily bearded Nowak), the episode does a great job setting the stage within its meager twenty minutes. In that regard, its characterization of Ocza is its most significant accomplishment. His eyes are perpetually downcast. Katsuyuki Konishi voices him like he’s on the verge of tears. The opening flashback affirms he bore witness to the same horrors Rafal saw, but Ocza sought a refuge in religion that ended up terrifying him even more. He’s also a talented swordsman. While this episode looks rougher than the previous ones, it pours its resources smartly into a quick and well-choreographed duel. This is the kind of directorial decision that makes me optimistic for the rest of the season.

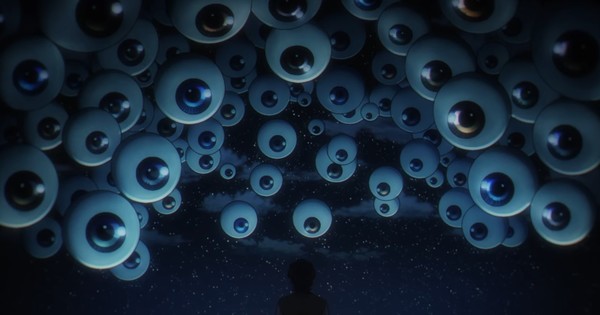

Orb continues developing its religious and scientific dialogues as well. In fact, it pays particular attention to how each informs the other. The monk uses the phenomenon of gravity to explain why Earth is more accurately described as the bottom of the universe, plagued by evil. Gras, choosing to look on the brighter side, instead takes the apparent perfection of the heavens to be evidence of God’s benevolence. Ocza comes to a conclusion befitting his dourness—the constancy of the stars is too much for him, and he instead imagines them as eldritch eyeballs peering down and judging him for his unworthiness. There’s one constant in all of these cases: their personal biases. These each inform their takeaways, and that’s bad science.

Gras provides the most straightforward example of observer bias. He collects his data diligently. He’s invested in the process. He’s excited about it. However, he presumes a conclusion without having the full picture. This isn’t in itself a crime. Science is all about hypotheses, and if a planet traces 90% of a circle in the sky, it’s reasonable to conclude it’ll finish the job when it doesn’t, though, Gras falls into despair. This is a human reaction. We seek patterns, and we don’t like it when there are none. This is also the irony of geocentrism. It posits a beautiful universe with everything in its right place, but the universe doesn’t follow those rules, and thus it appears ugly.

The truth, of course, is that Mars does abide by a set of rules and patterns that we’ve come to understand quite well. It’s not the firmament described in the Bible, but it has its own beauty. Moreover, it’s beautiful only because we can observe it as such. The universe simply is. That’s it. But to paraphrase Carl Sagan, humans are a way for the universe to comprehend itself. That’s a thought and philosophy I love a lot. To take another perspective, our spaceward observations confirm how astronomically precious life is on Earth. On a universal scale, life may very well be common, but our existence is balanced on the head of a pin. When the heretic speaks of beauty on Earth, he’s likely echoing either of these sentiments. And when Gras cuts his bindings, he confirms that he hasn’t fully given up on understanding the heavens. There’s a scientist in him yet.

I might have been a little apprehensive about how Orb would follow up last week’s twist, but this episode has convinced me that it knows where it’s going. It’s just like observing the planets. Mars looks like it wanders haphazardly across the sky, but it has a path, and it follows it.

Rating:

Orb: On the Movements of the Earth is currently streaming on

Netflix.

Steve is on Twitter while it lasts. He is busy pondering the orb. You can also catch him chatting about trash and treasure alike on This Week in Anime.