The manga project keeps on going! For a good month we’ve taken a look at people in the manga industry and have asked them for advice on their profession. Letterers was the first entry, followed by translators. Now, it’s time for manga editors!

I don’t doubt any of you know what an editor has to do. However, are you certain you know everything a manga editor has to do? Well, let’s find out! I got in touch with editors from Viz, Digital Manga, Kodansha, and a few others to take part in this. Here’s their answers to my questions:

How did you get the opportunity to start working as a manga editor?

Daniella Orihuela-Gruber (Hetalia, Sailor Moon): My major in college required that I do an internship in order to earn my degree, so I applied to internships with Viz and TOKYOPOP after I figured out I wasn’t interested in traditional journalism. I wound up getting the TOKYOPOP one after a bit of pushing. With Viz, I applied to the magazine internship (back when they had print magazines) instead of the editorial internship because I thought the magazine one would compliment my studies more. That was a mistake! It’s best to know what you’re really interested in when applying for an internship.

Lindley Warmington (Snow and Kisses, Welcome to Nyan Cafe!): I got the opportunity purely by chance. I knew that DMG had plans to hire scanlators in the near future, and then a friend emailed me when the hiring actually started. I was really excited when I was chosen.

Pancha Diaz (Midnight Secretary, Millenium Snow, Skip Beat!): When I was in grad school a local paper ran an article about Viz. I was already familiar with the company because they published all my favorite manga, but I’d assumed they were located in New York. When I found out they were in San Francisco, I checked the Jobs section of their website on a whim. There was an internship opening, which I applied for immediately. As my internship was winding down, one of the editors quit, and my supervisors asked if I wanted the job. My answer was YES! I worked part-time until I finished my degree, and then became a full-time editor.

Carl Horn (Banana Fish, Oh My Goddess, Neon Genesis Evangelion): My first professional editing job was in 1995 as an assistant editor on the former Viz Media magazine Animerica, which covered anime and manga on a monthly basis. At the time, the original Neon Genesis Evangelion TV show was in early production, and I covered its progress for the magazine. In 1997, Viz began to release the Evangelion manga, and my editor-in-chief on Animerica, Trish Ledoux, who also edited manga at Viz, asked me if I would like to try editing Evangelion. That’s how I got started with manga on a professional basis.

Ben Applegate (Attack on Titan, Battle Angel Alita: Last Order, Unico): I got into editing through journalism, working for English-language media in Korea. On the side, I got started doing manga and light novel translation for Seven Seas and Digital Manga Publishing. I also worked for Digital Manga running their Pop Japan Travel division for a while. So DMP head Hikaru Sasahara already knew me when he gave me my first part-time manga editing gig, running DMP’s Kickstarter campaigns for Osamu Tezuka manga in 2011 and 2012. Later that year, I moved to New York and took a full-time job editing Kodansha Comics manga.

Having an editorial background outside manga definitely helped, I think. Manga editing involves taking on a lot of projects at once on very tight deadlines, so in terms of daily workflow it’s actually closer to journalistic editing than to book editing. My experience copy editing also came in handy, because manga publishers don’t usually invest resources in an actual copy editor, so you’re expected to do both tasks.

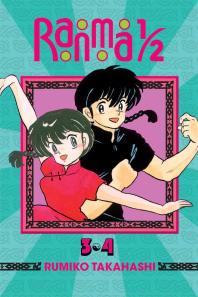

Hope Donovan (Kimi ni Todoke, Ranma 1/2, Toriko, Seraph of The End): I got an internship at TOKYOPOP between my junior and senior year of college. TOKYOPOP had an aggressive summer intern program. There were five of us in the editorial department alone, and somewhere around 20 at the company. Probably one of the reasons I got the internship was because I had editorial experience in college – I was the editor of DUIN (the school satire magazine) and the fine arts/literary journal, as well as the school newspaper’s cartoonist.

I kept in contact with a couple of nice editors at TOKYOPOP, Tim Beedle and Paul Morrissey. The next year when I graduated, Tim helped me apply for a copyeditor position that happened to be opening up. I was a copyeditor for a year, then was promoted to junior editor, then editor.

Rachelle Donatos Lipp (DMG Editor): While wandering the internet looking for possible opportunities to enter into the unbelievably tiny manga industry on the west coast of the United States, I came across DigitalMangaGuild.com. It was very easy to join, take the aptitude test, and begin working on assignments. While the pay is minimal, the experience is absolutely invaluable. I feel that Digital Manga Guild is the place where I’ve been able to successfully combine my editing skills with my obsessive love for manga, essentially turning this into a hobby that I now get paid to enjoy.

John Bae (One Punch Man, Nisekoi, Stealth Symphony): Before Viz, I worked as a book editor for 3 years. I also lived in Japan for 3 years. VIZ, to me, was the perfect opportunity to combine the two, so I applied to every editor position they put up, until they hired me!

If there was one misconception you had about the manga industry before you started working in the industry, what was it?

Daniella: That everyone would be an anime/manga otaku! I figured that no one would want to work there if they didn’t like anime and manga. But back then I didn’t understand a single thing about how businesses were run, so of course I was a little surprised.

The truth is that everyone on the editorial team was into manga, but everyone else in the company was not necessarily otaku. Some people were geeky for other things though. One of the graphic designers had an awesome collection of Doctor Who toys on his desk.

Lindley: The biggest misconception I had was that this job would be easy. I thought I’d be a good editor because I spotted all sorts of spelling and punctuation errors in published manga all the time; however, the job is so much more than skimming for such minor errors. Editors also have to do a lot of rewriting so that the book makes sense to Western audiences. I spend hours saying the dialog out loud to myself over and over again to make sure everything sounds natural, writing and rewriting the same line thirty times because nothing feels right, or brainstorming ideas for alternate translations back and forth with the translator. None of this work is visible in the published book. A lot of hard work goes into editing, and I never really appreciated it until I was the person doing it.

Pancha: That all the publishers were located in New York!

Carl: The basic principle that defines the English-language manga industry isn’t that you are translating, lettering, and distributing a manga. Those are all necessary and important tasks, but to become part of the actual industry, you also agree to do those tasks with the permission of the original Japanese publisher–just as the original Japanese publisher had to get the permission of the manga creator to first publish their work in Japan.

The Japanese have the right to choose whom they want to work with, and on what terms–and to be in the manga industry means respecting that right. Much of the time, most of the time, you will be able to both work something out together, and it’s on such a basis of mutual respect that manga created for Japan can also be found in stores across North America. I’ve walked through bookstores in the U.S. with visitors from the original Japanese publishers, and it’s a good feeling to show them their manga, and know that we all worked toward this together.

But to be in the industry also means accepting that sometimes it won’t be able to work. There have been times where I’ve asked if we can publish a certain manga in English, and for various reasons either the Japanese publisher or creator will say no. As a fan, I’m certainly disappointed, but, oddly enough, I also feel good as a fan to know their true feelings, and to respect their choice.

Ben: To be totally honest, I didn’t read a whole lot of manga when I first got into freelance manga translation. I was mostly into anime. I’d read a few classics like Ghost in the Shell and Akira, and a few manga in Japanese like GTO and Azumanga Daioh, but mostly the only Japanese books I read were on politics or history. When I did start reading in earnest, in 2009 or so, it was mostly older stuff like Tezuka, Keiko Takemiya, and Yoshihiro Tatsumi. I also devoured Urasawa’s Monster. In other words, I didn’t have too many preconceived notions going in.

Something that did surprise me was how little artists are paid when they’re just starting out. An artist who doesn’t have a tankobon out is a similar situation to someone trying to break into stand-up comedy. It’s not pretty.

Another thing that surprised me, though it probably shouldn’t have, was approval processes. I knew that Japanese artists retained most of the rights to their work, and that impressed me, but I was shocked at how practically everything, even something that almost anyone would consider trivial, needed to be approved by the Japanese editor or artist. That’s totally different from how most licensing relationships are handled in the U.S., and it can be a major bottleneck. I’ve been very lucky to work with people at Kodansha and Tezuka Pro who are laser-focused on getting books done efficiently and with a high degree of quality.

Hope: I had no idea what to expect. The only job I’d held before was a summer job working concessions at a movie theater. I hoped that I’d be on the cutting edge of a new field (this was 2004-2005 during the height of the manga boom). I thought the industry would continue to move up and up and I could feel like I got in on the ground level. I thought I could witness something that had never been done before. Now that I have more perspective, I realize that industries or interests like this pop up all the time. Just because something’s super popular now doesn’t mean interest in it will last. We’re still figuring out now in 2014 what the future of the manga industry and fandom will look like.

As for actual misconceptions, I guess I thought there’d be more training. But back then, no one knew anything about editing manga – we were all doing it for the first time. So there was a lot of learning on the job. I don’t think I received any formal training.

Another misconception was the idea that all manga is good. When you start getting into anime and manga, it really blows your mind. I had no idea how boring, lackluster and cliché so much manga is. As a copyeditor, forced to read every title going to print in a given month, you get an idea of how really awful a lot of it is. TOKYOPOP licensed a glut of titles, and so a lot of it was not worth your time. VIZ, where I work now, is much more careful about licensing worthwhile titles and it makes a huge difference.

The third was how much is changed for an American release. You take something that is original and complete, break it into tiny pieces, and then reassemble it. It’s painstaking art reconstruction work. At TOKYOPOP I was incensed at the changes – particularly the loss of art at the edge of the pages due to scanning rather than using digital files. There was also the fact that you can’t make a 1:1 translation all the time. You try to be as accurate as possible but sometimes that means staying true to the intent and flavor, not the literal translation.

Rachelle: I cannot say that I have or ever had any misconceptions about the manga industry. I entered this industry knowing that it would be like any other job: if you want to put out work worthy of praise, then you have to work hard. However, I can say that all too often contributors (everyone, not just editors) demean manga as just some frivolous picture book. Manga, though short in length and filled with pictures, should still be handled in the same manner that one would handle any other published piece of literature. You do this for the authors and illustrators who poured their lives into each book, and also for the readers who paid for this piece of fiction. This line of work is not always an array of fluttering roses and bishounen as many often imagine.

John: Since I wasn’t into manga and anime before working at Viz, I really didn’t have any preconceived notions about it.

What’s generally the biggest challenge you face when editing a manga series?

Daniella: Trying to catch the right tone for the series is probably the hardest for me. The copy-editing, the formatting, and the quality control aspects of the job are all pretty easy, but finding language that fits the book the best is always a challenge.

You have to find the right balance of language befitting a character and the overall tone of the manga. This is less about localization or writing the character like they’re speaking in an accent, and more about making sure a trendy teenager in the 21st Century isn’t speaking like they’re a Victorian aristocrat. Unless the manga tells us that’s their thing.

It’s easier if there’s a re-writer on the manga, though. That way there’s two of us trying to get the language right. However, I don’t always get that privilege!

Lindley: I’ve actually never worked on a series yet. All of my projects so far have been one shots. But my biggest challenge with editing a manga is doing quality control. It’s really easy to focus and actively read when I have to switch between script and raw PDF, but it’s so easy to be swept away by a manga after it’s been lettered. I have to take several breaks while I work and I try to avoid QCing more than one chapter per day in order to avoid zoning off while reading.

Pancha: Almost inevitably a lack of time. We have to wait for contracts to be signed before we request assets, and then wait for assets to arrive, and then the translators and letterers need time to do their jobs. All that completely eats up what might seem like a long lead-time. Then our distributor needs the physical books a certain amount of time before they go on sale so the books can be shipped out, and the printer needs the files a certain amount of time before that so they can fit in the printing queue, and you need to get the files to pre-press before that… Managing your schedule is one of the most important parts of the job, and not to be taken lightly.

Carl: In terms of the industry, scheduling. A volume of manga (tankobon) starts off as something you can buy in Japanese in a Japanese bookstore, but my job is to turn it into something you can buy in English at a North American bookstore. Naturally, your manga is one of only many books in that store, so in order to get it on their shelves, you have to follow certain rules as a publisher–most importantly, setting a date for the book’s release and then making sure you actually do get it to the store that week. If you don’t make it on time, then they have to change their plans just on your account (remember, they don’t have unlimited shelf space–it’s like making a reservation and then not showing up when you said you would), and in some cases they might have the right to cancel their order of your book.

So the biggest challenge is to meet that commitment, which means picking a good future date to release the book. It should be “good” in a number of different ways. First of all, does that date give you enough time to do all the tasks you’ll need on that particular book–acquiring raw files from the publisher, translating, lettering, designing the book, proofing, printing?

Second, beyond that particular book, did you pick a date that will allow you to balance the overall workload at your company? What I mean by that is, Dark Horse releases hundreds of separate books a year, only some of which are manga. An editor can’t produce a volume of manga all by his or herself, but also needs to work with designers, digital art experts, pre-press specialists, etc. All of those people will be working on other projects besides your manga, so you have to take into consideration their work load.

Both external scheduling (getting your finished book to the printers, distributors, and stores) and internal scheduling (getting the book finished) are very important. And of course, most manga series are more than one volume, so at the moment that English vol. 1 finally hits the stores, you may be proofing vol. 2, starting to translate vol. 3, and writing ad copy about vol. 4. In other words, it’s an ever-rolling process. To be in the manga industry means to accept these commitments and stick with them.

Ben: The complex challenges include catching little translation errors, translating puns, and romanizing names written in katakana, but I see stuff like that as puzzles to solve, and I actually really enjoy them. Probably the toughest thing is keeping track of character names and voices. Where a more traditional editing job calls for you to do a few books at a time, a manga editor might be working on four or five different series in a week, all tied to previous and future volumes, which makes it extremely difficult to keep dialog quirks and name spellings in your head. You’ve got to write that stuff down or it’ll slip your mind. To alleviate that, I try to carve out a day or two to edit a single script before it goes to the letterer, which helps me focus a bit more, though I haven’t had time to do that lately.

Hope: Deadlines. Most editors are perfectionists. If we could spend months massaging a script and layout until it sparkled, we would. We’d love to give our translators and letterers all the time in the world. But we are in the business of book production, and you have to churn out a new volume in the series every couple months. The whole business is predicated on you hitting your schedule. Sometimes there are drop-in titles that are an extra rush.

I look at it like a challenge. It’s the work that you can do under tight deadlines and high pressure that counts, not the work you can do under ideal conditions. I think that’s something that’s true for all working people.

Rachelle: The biggest challenge I face every time I edit a manga series is making sure that I’ve not edited away something the author wanted in the story. Essentially, I battle the concept of “lost in translation” often. Nuances that are found in one language do not always translate into English. It’s in these times where an editor’s people skills come in handy; one-on-one with the translator is typically the only way to solve this dilemma.

John: Definitely the sound FX. Japanese uses a lot of onomatopoeia in their language, and, more often than not, there’s no real English-language equivalent. Also, specific references or jokes that involve intimate knowledge with Japanese culture is often hard to get across to foreign audiences.

If there is one thing an editor must keep in mind when looking over a manga, what is it?

Daniella: How the reader would react to reading a manga. Would the way this sentence is written confuse them? Does it flow nicely? Is there some way to make it better? Will the reader notice if we had to retouch the art here or there? Etc. Etc. Etc.

Lindley: Definitely sound effects. They’re really sneaky because I tend to ignore them when I’m reading manga casually. A lot of friends have told me that they have the same habit. Sound effects are just really easy for everyone to overlook, and that leads to things like spelling errors or untranslated sound effects going unnoticed. I’ve had to retrain my mind to pay more attention to sound effects.

Pancha: When we look at a new series to acquire, one of the first questions we ask is “will this sell?” And sometimes even if the series is amazing and one of the best things we’ve read in a while, it will still be too niche or otherwise unlikely to sell. It can be hard to pass on something you love, but we have to keep the realities of the market in mind at all times. We can’t let our fan-selves make all the decisions.

Carl: I think one approach is to not just look at them from the outside, as characters and scenes on a manga page. Imagine an “inside” view instead; see these not as characters and scenes, but as people and moments. From the outside they’re in a “story,” but from the inside they’re in a situation. Maybe sometimes the situation is (just as real life can be) strange, silly, absurd, or even dumb, but as an editor, you should have empathy toward any manga you work on.

Ben: Like with all editing, it’s never just one thing, but there are different things I keep in mind at different points in the process. When I’m editing a script, I’m on the lookout for translation errors, and I rewrite liberally to make the lines read better. When a first pass comes in from the letterer, I’m looking for things that just look bad on the page (i.e., a line that just doesn’t fit into a bubble properly or art problems like bleed), and I’m still rewriting awkward phrases. On the second (and third pass, if there is one), I’m totally focused on eliminating typos, since any major changes that late in the process can introduce errors rather than fixing them. But really, you have to be ready to fix any kind of problem whenever you spot it.

Hope: Keeping fresh eyes for every read is essential. Every time you read a book (I generally read a book seven times throughout production), you have to approach it like it’s the first. You can’t let your eyes glaze over or your mind wander. So having that focus and dedication needed to read fresh is really important.

Rachelle: Readability. Bottom line is that readers fuel the publishing world. Your efforts translate into their enjoyment of the book. Their enjoyment of the book translates into potential profitability. In other words, if the reader enjoys the book then you’re likely going to be busy as additional volumes to that book are licensed for publication.

John: Everything matters! From the dialogue, to the placement of dialogue, to how the FX is placed within the context of the art, etc. Manga editing entails so much more than just looking at a script.

What would be the best way for an editor to break into the manga industry?

Daniella: Get. An. Internship. Manga editors in the states tend to come from very different backgrounds, so the best way to get the skills and training for this very specific job is to be an intern and learn the actual job.

And when you get that internship, make sure they don’t put you in the mail room too often. Push your superiors to teach you what they’re doing! Dazzle them with your passion for the job so that they have no choice but to offer you paid work after your internship ends.

Lindley: Freelance! Freelancing is a great way to get into the manga industry. You can work on your own schedule and often have some control over what titles you want to do. Freelancing also helps you get experience in the field to help make your resume look better and helps you get connections. Most importantly, freelancing will let you find out if this is really the right job for you before you spend a lot of time and effort on getting a full-time position.

Pancha: The manga industry is still pretty small, so the number of editorial jobs is limited. Keep an eye on company job listings so you can jump when an opportunity presents itself. And while you’re waiting, hone the skills that will make you a good editor and acquire all the experience you can, even if it’s with personal projects. The reason I was able to step in when an editorial position opened up is because I had already done other internships, freelance copyediting, and various editorial projects stretching back to high school.

Carl: English skills are important, and I also recommend getting journalism experience. In my case, it was with my high school and college newspapers, but of course there are other venues for journalism online. Why is journalism a good training ground for a manga editor? As a manga editor, your job will be to make sure these manga both a.) communicate well in English, and b.) do so while meeting their scheduling requirements. A journalist who works for a regular newspaper, magazine, site, etc. has to do these same things, so if you can show that kind of experience on your resume, it will demonstrate you understand what’s needed to be in the industry.

By the way, I think this applies whether the kind of journalism you do is specific to Japan or not; in other words, it doesn’t necessarily have to mean getting involved with an anime magazine or newssite. After all, one of your goals in the industry should be to reach people who aren’t currently manga fans, but who might discover or become interested in a manga you happened to edit. When I was working for my school newspapers, the idea was to be able to communicate ideas to everybody reading, not just hardcore fans. Manga in America isn’t like TV or movies, something everyone is into. Only a tiny percentage of Americans read manga on a regular basis. If you want to get into the manga industry, you should want to change that; make more people here fans. We still have a lot of work to do!

Ben: Get a job as an editor. There are fewer and fewer editorial jobs these days, but they’re out there, and it’s still much better to have the résumé of an editor and a passion for manga, as opposed to a résumé full of manga-related jobs that have nothing to do with editing. The exception would be if you came at it through translation, since I do know some editors who broke in because they were excellent translators, even though they lacked editorial experience.

An absolute requirement is that you must study Japanese. In the old days, it was possible to be a manga editor without literacy in Japanese, but today I think that’s just impossible, which is as it should be.

Hope: Demonstrate to a company that you have project management skills along with creative writing skills and a passion for manga. Knowledge of Japanese and art design doesn’t hurt. When companies hire editors, it’s a lot like hiring any other middle manager in any company. So there will generally be job postings online. Keep on top of those. Also, because manga editing is an incredibly specialized field, getting experience in manga editing or editing is good. Find an internship if you can. There are manga publishing houses on both coasts. Keep in mind that you’ll probably have to live in those areas if you want to edit manga.

Rachelle: While felling I’m like reciting some plug on a television show, even though I’m not, I would say that the best way for an editor to break into the manga industry is through a company like Digital Manga Guild. It is the ideal setting for an editor with little to no experience to see firsthand what being a manga editor is all about. Once they’ve gained plenty of experience through a company like Digital Manga Guild, they can then apply to any open job opportunities with verifiable work experience.

John: Obviously, any editor in the U.S. needs to have a strong English-language background. But for manga, intimate knowledge of the language and culture is a definite plus.

What type of advice would you give to someone who might be interested in this venture?

Daniella: If you’re determined to be a manga editor, be prepared for three things: That you won’t be working as a manga editor for a company in Japan, that you’ll probably be working as a freelancer, and that you really should learn Japanese.

The first one is obvious: People like to dream big and think they’ll wind up breaking into the industry in Japan. Breaking into the industry in the U.S. is a lot more realistic and doable. Which isn’t to say that you won’t ever make it in Japan, just that there are a lot of hoops to jump through.

Second, be prepared for the hard life of a freelancer because you will be freelancing at some point in your career unless you have the luck of the gods. You will probably need to get other work too, so be prepared to get freelance gigs, part-time jobs, or even full-time jobs that aren’t in anime or manga. There are people out there who translate anime and manga, and hold down full-time jobs as veterinarians. Even I, after a few years of trying to freelance full-time, now work full-time at a travel agency and do freelance manga editing in my spare time.

Lastly, learn Japanese. Learn Photoshop and InDesign so you can letter manga or design the covers. Learn any skill that might make you seem more attractive to employers in the anime and manga industry. You might not be required to have those skills for manga editing, but they might get you a better job or more freelance gigs. With this economy, it’s a good idea to have a wide range of skills no matter what kind of job you pursue.

Lindley: The best thing to do is to learn Japanese and Photoshop. Learning about Japanese history and culture also helps. Knowing Japanese helps with the rewriting process. Also, being able to understand Japanese means that missing lines or sound effects can be quickly added (though I always mark my additions so that the translator can double check the new lines for accuracy when reviewing my changes). A background in Japanese history and culture can also help with rewrites, particularly with lines that have cultural references in them. Knowing Photoshop can help when making requests to the letterer. Knowing the names of the tools or the name of the specific task means that the letterer can jump right in and get started instead of spending a lot of time asking/clarifying questions.

I once worked with a letterer who didn’t speak much English. She couldn’t understand what I was trying to say, so I photoshopped a small part of the page as an example and sent it to her. From that image, she knew exactly what to do and did a great job of it. Also, a lot of full-time editing positions require a background in Photoshop and InDesign, so learning these two programs can help you secure a full-time position. Because an editor’s job takes place between the translator’s job and the letterer’s job, my personal opinion is that the editor should be a jack-of-all-trades of sorts – not necessarily good enough to do the other jobs alone, but at least good enough to help make everyone else’s jobs easier.

Pancha: Get some sort of English degree—Lit, Creative Writing or Journalism are all a good basis for an editor. Learn some Japanese, even if it’s just how to read hiragana and katakana. Even just that much familiarity helps you with missing sound effects and checking that names are spelled correctly. Fluency is a big bonus!

Learn the basics of Photoshop and InDesign. This helps you communicate better with your designer and letterer, and lets you make last minute changes yourself.

Carl: If you really want to become part of the manga industry, it’s also worth considering starting your own small manga publishing business. There’s two reasons for that–one, it would give you an additional option in case you can’t find a place at an existing company, and two, it would mean you yourself are doing something to expand the manga industry.

You don’t necessarily have to go it alone, either–you may have resources you don’t know about. For example, suppose you’re a college or grad student right now. Lots of colleges publish books, and some have even published manga in English. If your university has a publishing division, why not look into it, and see whether you could find a manga that would be a good project for them, perhaps in cooperation with a suitable department at your school–it could be something done for Japanese studies, media studies, literature, or even other areas of study. If the project works out–and even if it doesn’t work out–you’ll be learning things and getting experience that would definitely boost your resume if you wanted to try and work for a manga company later on.

Ben: This is a difficult point to explain, but: Love editing more than you love manga. Don’t get me wrong, I love manga, but if your passion for the material overwhelms your passion for the job, you’re going to make bad decisions and put yourself and your colleagues through unnecessary stress. You must be able to evaluate different parts of your job as an editor first, not a fan. Looking back, I made my worst mistakes because I let my fan excitement overcome my professional judgment. Get your priorities straight, and everything else (healthy workflow, good office politics, communication with freelancers) will fall into place. It won’t be easy, but at least you won’t be making it harder for yourself.

Hope: Stay a fan. It will give you the energy and community you need. Once you start to see manga as a business, even just seeing the nuts and bolts in action, it will disillusion you. But if you can still care about manga as a fan, you’ll feel stronger and be better positioned to make decisions about manga. Once you’re in the industry, you can stay there if you work hard. The question will be, will you want to? Most manga fans drop out in their early 20s. You’ll have to commit to being someone in their 30s, 40s, 50s who passionately cares about manga.

Rachelle: There are three bits of advice that I’d give to anyone seriously interested in becoming a manga editor. Firstly, invest in an extremely comfortable chair because you’ll be spending quite a bit of time in it. Secondly, take breaks. There is nothing more detrimental to your editing capabilities than an overworked mind. Thirdly, feed your love for manga. If you stop reading for enjoyment, then you could lose the connection that you feel to manga. That connection is what led you here seeking advice, and is pushing you towards becoming a manga editor. When that connection is lost, this becomes just another job and the pay at this level isn’t worth your time.

John: Don’t limit yourself to reading just manga. Learn about Japanese culture and language.

(c) Organization Anti-Social Geniuses – Read entire story here.