© Anime News Network/White Box Entertainment

Anime has never been bigger in the United States of America. It’s a big statement to make but relatively easy to qualify. According to research from Polygon from 2023, “56% of Gen Z respondents and 41% of Millennial respondents say they watch anime at least once a month” with the supermajority of that Gen Z audience watching anime weekly. This more-or-less lines up with data from industry-leading researcher Morning Consult in 2021 which indicated that more than a third of adults in the States have a positive impression of anime.

The anime industry now generates a majority of its total revenue outside its home country, per The Association of Japanese Animation. With California-based companies like Crunchy Roll and Netflix grabbing a massive share of international distribution deals and the U.S. branches of distributors like TOHO and Toei Animation massively expanding their roles in the country’s anime ecosystem, the United States is more relevant than ever.

Like any other expression or art form, different cultures engage with anime in various ways. To better understand the anime audience in the U.S., we’ll explore the differing tastes of the latest simulcast season here compared to the Japanese audience. While currently airing titles do not make up the majority of anime consumption in the U.S., it’s one of the few parameters allowing apples-to-apples comparisons across countries, providing context in a world where publishers carefully guard viewership numbers.

I previously shared a comparison between the two countries for the previous simulcast season. In that analysis, I looked exclusively at the estimated audience size. While I had confidence in the math that went into the U.S. numbers, I had to rely on just two data points on the Japanese side: viewership, as reported by Abema TV and Niconico. As I discussed – and as many commentators were eager to point out – this was not an ideal practice. In Japan, anime is typically not exclusive to certain platforms, is watched on TV (frequently recorded and viewed later due to the inane broadcast times of most anime), or streamed across dozens of services that all have their means of monetization and holdback from initial broadcast.

So if not viewership, how do we determine popularity? It’s easy to think you know what’s popular, but our experiences are fundamentally biased. We generally spend time in person with people who live in our community or close to it, who are our age, and who have reasonably similar interests, values, hobbies, or the like. Our online lives are sorted into niches of those who opt into the same Discord, website, or forum. Social media is governed by algorithms, segmenting what it shows us based on what it thinks we’ll like or what our friends have already engaged with. Even what’s displayed as a “trending” topic is programmatically adjusted to you.

And this challenge is more profound because anime stretches across demographic groups and genre interests. The kind of people who track each episode they watch on MyAnimeList have meaningfully different viewership patterns to those on AniList. Yet, added together, they’d represent a smaller share of the anime audience than the people who keep track of what they’re watching on a notes app or in a journal, a smaller cohort still than those who YOLO through life and trust themselves and/or their service of choice to remember where they left off.

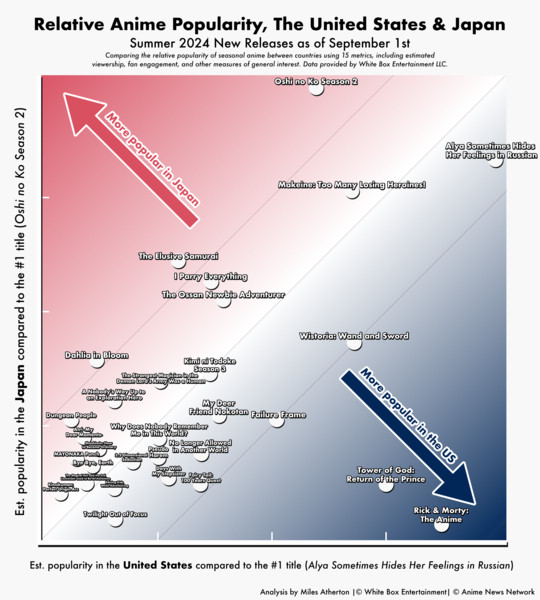

So, to abstract “popularity” into a number that is comparable across different cultures, my team at White Box Entertainment pulled in 24 metrics for the U.S. market and seven in the Japanese market from public data sources that we’ve found to be predictive of “popularity” in previous seasons and similarly weighted them to what was described for last season’s analysis. This popularity ranking still weighs estimated viewership much more than any other element, but now factors things like search volume on Google and YouTube, how much engagement anime is seeing from fans in online arenas, and how much interest audiences show for English-language news related to the anime. This popularity is on a relative scale of 1 to 100, where 100 represents the total of each metric for the top anime in each respective country.

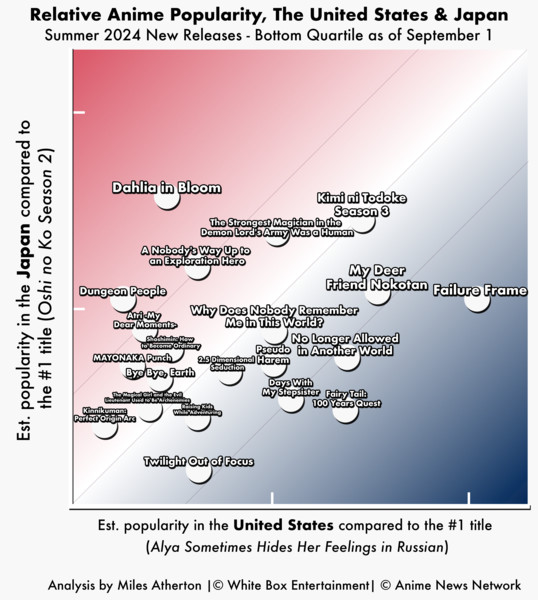

Most of these metrics used are from the internet, where political borders are of little importance. So for statistics where we had data about the geographical distribution, we adjusted for the share of Americans out of the total English-speaking audience accordingly and did the same for Japan. It’s not a perfect method, but it’s more robust than a simple estimate of unique viewers and acknowledges the audiences with outsized passion for their favorite show. The results can be found here:

© Anime News Network/White Box Entertainment

The x-axis here represents the estimated popularity of a summer anime in the United States on a scale of 0 to Alya Sometimes Hides Her Feelings in Russian, while the y-axis is Japanese tastes on a similar scale with Oshi no Ko‘s second season as its scion. The deeper a title gets into the red color, the more disproportionately Japanese audiences are engaging with a title, while the reverse is true for the U.S. audience and the color blue.

While most titles fall within the faint purple lines that show a 25-point absolute popularity difference, there are still meaningful differences in reception across territories demonstrated within. For example, Atri is a little more than three times more popular in Japan than in the States, so we’ll be zooming in on the bottom quartile later to highlight some of those disparities.

Viewership Remains Concentrated in Top Titles

In the analysis of the spring season, even after removing the uber-popular outlier Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba, U.S. viewership was highly concentrated on just a few titles, with the rest of the 50+ anime of the season receiving only a fraction of the audience. This is expected behavior: only a half dozen or so anime in a given season see meaningful promotion in English-speaking territories thanks to corporate consolidation, diminishing marginal returns, and the general lack of marketing towards anime titles from broad-market streamers like Netflix and Disney. Additionally, the U.S. has a less mature anime market than Japan. A larger share of the anime community here is still relatively new to the medium, so they’ve had less time to branch out and explore.

However, for the summer season, both Japan and the U.S. have similar consolidation at the top: only five series each have at least half the popularity of their country’s favorite.

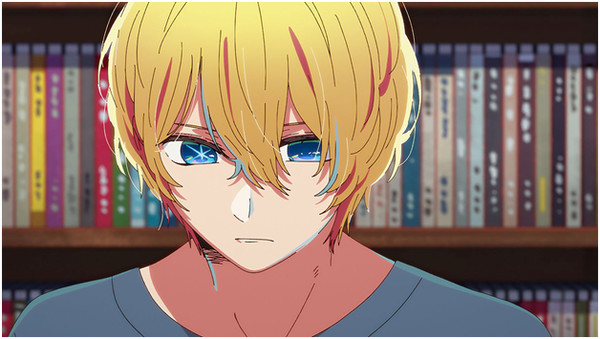

© ????×?????????????????????

The biggest reason for this is the most straightforward: Oshi no Ko Season 2 is unbelievably popular in Japan, distorting the relative popularity of every other title around it. If we were to use estimated viewership as our only metric of comparison as with the last season, the chart would be unreadable; none of the July anime lineup has even half the viewership of Oshi no Ko in Japan.

This ties into another important factor: using the popularity metric over estimated viewership blends different measures of engagement and dulls the extremes. Makeine: Too Many Losing Heroines! has become a sensation in the fan community across borders, receiving full-throated acclaim from fans, critics, and influencers alike. Even the least engaged anime fans cannot escape the fanart on social media. Oshi no Ko is getting many more views than Makeine in Japan, but the difference in depth of fan engagement between the two is not so dire, which closes the space between them in terms of evaluating overall popularity.

Lastly, there are a few standout series this season. Oshi no Ko and Tower of God are the only major sequels released with built-in fanbases, and the top anime in the United States is Alya Sometimes Hides Her Feelings in Russian, a title that, before its well-received PV, was all but unknown. Compared to any other season in the last few years, the July season had fewer franchises. It encouraged audiences to branch out more than usual.

General Trends

I’ve been comparing these kinds of trends using both public and private data for over a decade at this point, and the biggest dichotomy across these two anime audiences that’s been consistent the entire time is the split between anime that are plot-focused and character-focused.

American audiences have a conception of anime tied to the specific series that made the medium popular here in the first place: the battle-heavy serialized tales of heroes like Goku in Dragon Ball and the mind-bending storylines of Akira still resonate as what defines the whole of Japanese animation to this day. This is not a totalizing mentality, but it is a pluralistic one.

There’s a conception in the industry in Japan that Western audiences don’t like “slice-of-life” stories. While this is broadly the case, some of these titles have such disproportionately passionate fanbases that they can sometimes grow to near-mainstream importance. A great example of this is last year’s Bocchi the Rock!, which experienced an organic wave of positive buzz to go from a middle-of-the-pack title to a solid performer by the time it took home a prize or two from the Crunchy Roll Anime Awards.

Japanese fans demonstrate a greater interest in character studies and more introspective narratives. Again, this is a trend rather than a strict rule, but it’s hard to miss in the data. ATRI: My Dear Moments, SHOSHIMIN: How to become Ordinary, and Mayonaka Punch are all examples of these kinds of anime that see a large multiplier on the Japanese side of the chart, whereas Failure Frame, Fairy Tail, and Wistoria represent the penchant for serialized plots and high concept anime in the States.

Oshi no Ko and Tower of God

To take what we discussed in the previous section a step further: the notable successes of Oshi no Ko in Japan and Tower of God in the U.S. are the best case studies for understanding the dynamics at work here.

One of the most vocal complaints across the anime community is the lack of reliability in a series getting a sequel, particularly with the increased preference for 12- or 13-episode releases compared to decades past. With nearly every major anime studio booked several years out, production committees typically need to plan in advance of a first season’s release, whether or not they want to pursue additional seasons to meet a window where the franchise is still at its most relevant and get the most out of the investment. Even if the Studio Line is secured, maintaining the same creative team often requires a bit of flexibility.

© ????×?????????????????????

So it follows that anime fans are quite eager for second seasons that release within a year or so of the initial release. The typical behavior I’ve observed is sequel seasons have low churn and frequently even see some growth from positive word-of-mouth. Of course, for anime that isn’t popular to begin with, it’s much harder to maintain an audience across seasons–you have to get them to finish the first season to even consider another dozen episodes–but it’s rare to see the One Punch Man scenario with seasons that take place in back-to-back years.

In the States, Oshi no Ko Season 2 has been a decent performer but has been in no way the culturally dominant force its first season was. I’m doubtful we’ll see season 2 on The New York Times’ list of the best TV of the year, even if it’s nearly as deserving as its first go-around. Why is this?

Japanese cultural elements often present challenges for international viewers. From my experience in the industry, these issues are overstated or misunderstood by business people on both sides of the Pacific but can make it harder for a series to relate to its overseas audience.

Oshi no Ko‘s second season centers around a stage play adaptation of a manga. Attending a stage play based on an anime or manga franchise is not the most popular means of fandom expression in Japan (and they’re fairly rare outside of Tokyo), but they are a visible and present part of the otaku culture. There’s an awareness of them to a degree that’s not nearly as ubiquitous internationally, and this makes sense; most anime fans overseas don’t speak Japanese, and filmed performances are infrequently subtitled and distributed online. The show’s first season focused on idol culture more broadly, which, while still not well-understood by American audiences, was novel to viewers and had enough easy comparisons to Hollywood practices to provide comprehension.

Another factor I believe impacted Oshi no Ko‘s performance stateside was the lack of an opening sequence with music by YOASOBI. There aren’t many musical acts that can make people watch an anime, but YOASOBI is at the top of that list. The opening sequence for Oshi no Ko season 1 was a viral sensation, and its music was the de facto song of the summer for millions of anime fans, regardless of whether or not they had seen Oshi no Ko. Opening sequences rarely make-or-break for anime performance, but starting every episode with YOASOBI was a huge win.

The last point on Oshi no Ko‘s U.S. performance is related to its streaming exclusivity on HIDIVE. The service only has a handful of titles a season, so the size of an audience it can sustain is dramatically smaller than Crunchy Roll‘s or a service that has anime in addition to other entertainment mediums like Netflix or Hulu. A trend that’s accelerated in 2024 is U.S. streaming customers canceling one service to watch another, swapping between a few services at a time rather than try to maintain active subscriptions to the whole slate. This seems to have hit HIDIVE particularly hard, as even accounting for the platform’s decision to pull back service from most countries late last year, their U.S. traffic is down according to SimilarWeb.

©Netflix

In Japan, Oshi no Ko‘s second season was similarly a step down from the totalizing sensation it was last year, but the fandom is still incredibly vibrant, as seen by its dominating position in the popularity chart.

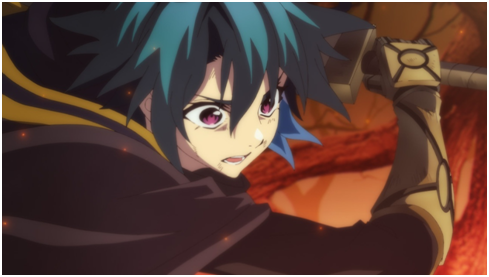

On the other hand, the first season of Tower of God was one of the few anime Crunchy Roll has co-produced where the fact is highlighted in their marketing. As a result, it received central attention on all of Crunchy Roll‘s platforms just as the lockdowns from the pandemic were kicking in and a swath of new and lapsed anime fans scrambled to find something to keep them busy. Besides being heavily promoted, Tower of God‘s first season was quite well received by fans and critics and seemed to indicate that the biggest WEBTOON properties would be getting royal treatment in their anime adaptations.

©Tower of God 2 Animation Partners

While it’s true that the most high-profile WEBTOON adaptations have been proportionately more popular in the West than in Japan – The God of High School and Solo Leveling join Tower of God in this respect – that’s not to say there’s not a large Japanese audience for these shows. As discussed last season, Solo Leveling was part of an erroneous online narrative that the series was deeply unpopular in Japan due to its poor home video sales. However, Solo Leveling was one of the most-anticipated anime of the season in Japan per Animate and scored high on many other engagement metrics we track.

But it’s unsurprising that Tower of God‘s second season was so much more popular in the U.S. than in Japan. While Tower of God was reasonably popular in Japan, it wasn’t a top 10 title in the Spring 2020 season, let alone one of the biggest of the lineup. It simply did not have as big of an audience to work from, and its drop-off between seasons is pretty normal for a show with a four-year gap between new episode releases. Americans, though, stuck around for the new season.

When I’ve shared the popularity analysis with others deeply involved in the English-speaking anime community over the last few weeks, Tower of God‘s second-place rank raises more eyebrows than anything else on the list. The anime’s high ranking in the U.S. is at odds with its reception among fans, both of the original webtoon and from its anime-only viewers. The Anime News Network community provides a great indication of this: Tower of God was regularly near the bottom of the weekly audience ratings, ending in 36th place in the cumulative tally.

So why is Tower of God so popular amongst Americans if it’s been so long since season 1, and if it’s not good? This is the most difficult behavior I’ve had to explain, and I have very little quantitative evidence to back up my assessment. I sense that it’s due to 1) the unique timing of the first season’s release made it much more resonate of a title in the American fandom, 2) the stark difference in storyline and focus characters was a frustration that forced viewers to stick around for the ending, and 3) the title reached far beyond the typical simulcast watcher into more casual anime audiences, who are more likely to weather through a bad season or two of a show that they’ve previously liked than people who test out a dozen new anime a season. For that last point, Tower of God viewers in the U.S. watched fewer simulcasts on average than any of the other top 30 new shows of the season after My Deer Friend Nokotan and Fairy Tail, which tends to indicate a more casual audience overall.

Rick and Morty: The Anime

© Adult Swim, Telecom Animation Film

According to analysis from ShowLabs via The Entertainment Strategy Guy, Rick and Morty: The Anime had an estimated 1.74M U.S. viewers on Max on its release week, making it competitive with the latest Last Week Tonight with John Oliver and the streaming debut of George Miller’s Furiosa. For context, this is around ten times the number of viewers Rick and Morty: The Anime had live during its terrestrial broadcast on Cartoon Network, as estimated by Nielsen Ratings. This is fairly typical for the timeslot, if a little low. There’s not much live engagement on cable in 2024!

Once we factor in piracy estimates, that brings the total viewership of Rick and Morty: The Anime to around 3M unique U.S. viewers for August. Almost 1% of the U.S. population gave Rick and Morty: The Anime a try! While the numbers took a sharp dive in September by all the metrics I keep track of, it’s not surprising that so many people would give the anime a shot in the first place. Rick and Morty is one of the most popular franchises in the States, ranked just outside of the top 100 of all contemporary shows according to YouGov and considered in the 99.99th percentile of “in demand” titles by Parrot Analytics, so even a spin-off with less-than-enthusiastic response from fans is going to capture a share of that audience. That pie is big enough that any slice you cut will be hearty!

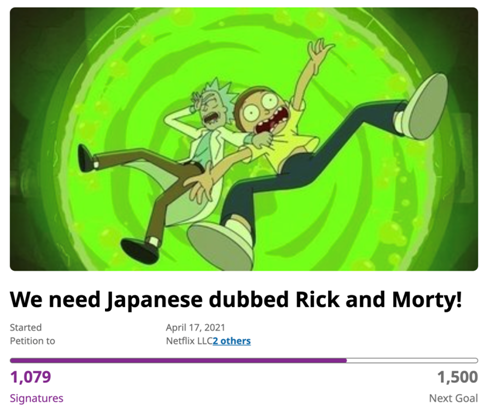

But leveraging the popularity of Rick and Morty is not nearly as easy for WarnerMedia in Japan. While the anime was dubbed into Japanese, that’s not true for most American Rick and Morty series. Only the first three seasons were localized, causing some fans to start a Change.org petition for the remaining five seasons to get their due.

.

That said, in the three and a half years since the petition was launched, the survey has received just over 1,000 signatures. This is representative of online discussion around Rick and Morty in Japan more broadly: it simply does not resonate as deeply as it did in its home country. There’s been very little chatter in Japanese spaces online for the title, and fewer still indicators of the vibrant fan culture we see for even the lowest quartile of seasonal anime.

To put a finer point on it: by our formula, Rick and Morty: The Anime is 52 times more popular in the States than it is in Japan. No other anime comes close: Tower of God is the next closest at 15x, and the biggest ratio in favor of Japanese interest is Dungeon People at 6x. Rick and Morty may be the most extreme outlier I’ve ever seen in this kind of analysis, but considering its background in both countries, it’s hardly a surprise.

The Elusive History of Samurai

Typically, we expect the total audience size of simulcast anime to decrease as the series goes on as people drop off, get busy, or forget to keep up. A reasonable portion of that audience will return in time for the finale (or binge the show once it’s complete), but a dip characterizes the middle month of a season. Not so for The Elusive Samurai . Thanks to strong word-of-mouth and highlights of the series’ exceptional animation going viral across social media platforms, The Elusive Samurai grew its U.S. audience by 20% month-over-month in August, but that still was not enough to compete with the feverish Japanese audience, which was 2.5x more popular in the Land of the Rising Sun.

© ?????????????????????

For international audiences, Japanese cultural elements and iconography can represent diminishing marginal viewership as they become more central to the anime’s story or aesthetics. These facets represent a big part of why so many overseas fans fell in love with anime in the first place but all the same, there is a point at which the potential audience size for a series begins to decrease as a particular anime focuses on less universal subjects.

A frequent comment I’ve seen on this topic with The Elusive Samurai is that viewers feel like they’re missing important context by only having passing familiarity with the Warring States. In my opinion, the show does provide the minimum background necessary. Still, it’s easy to feel as though not knowing the biographies of some key players beforehand will provide an incomplete experience. Additionally, there’s some predictive relationship between anime featuring a historical Japanese setting and lower viewership, holding for other factors.

©????????????

This is all to say that this is the most straightforward explanation as to why The Elusive Samurai is not performing better in the U.S. Weekly Shonen Jump adaptations have a rather high floor in terms of performance. This one does not have the excuse of being relegated to a streaming platform without an infrastructure for anime promotion like Mission: Yozakura Family. Anime with the kind of gorgeous action sequences like those in The Elusive Samurai tend to be reasonably popular stateside, and doubly so when they get love from streaming giant Crunchy Roll in email and social media marketing channels like Samurai has.

The lack of experience with Japanese history makes it harder to sell to large U.S. audiences, as has been the case for many period pieces before it, no matter how excellent they are. See Golden Kamuy, The Heike Story, INU-OH, Sh?wa Genroku Rakugo Shinj?, House of Five Leaves, and even Sengoku Basara for other examples of this, or if you’re simply looking for some of the best anime released in the last 15 years.

Wistoria: Algorithmically a Winner

Wistoria: Wand and Sword is certainly not unpopular in Japan – it’s a top 5 title by this analysis! – but leans heavily towards the American side of the chart. My primary explanation for Wistoria‘s 3.9x relative popularity ratio is the streaming service Crunchy Roll.

While the title was secondary to anime that over-perform with more general audiences like Kaiju No. 8 or Demon Slayer in paid media, events, activations, and brand collaborations, Crunchy Roll promoted it at a fairly high rate on their social media. However, I believe the most important promotional tool that helped Wistoria get an edge in the U.S. was an algorithmic one: their in-app experience.

© ??????? ???????????????????????

For full disclosure and context, I’m more than three years past my tenure as a Crunchy Roll employee. During that time, I started the team that would become the Curation department, the group responsible for programming titles displayed on the in-app experience. I won’t pretend to have any special insights into the various algorithms and best practices that go into what anime are displayed nowadays but one trend I’ve noticed seems to have carried over from my era: the most popular simulcasts are aggressively served to people who watch any amount of simulcasts. In a season without a clear winner, any title in the top 3 or 4 of the season will have a viewership snowball effect as the season goes on.

Surveys conducted by White Box Entertainment back this up: People who watch Wistoria are 31% more likely to have a Crunchy Roll subscription than the typical simulcast viewer. The relationship is strong in reverse, too; along with Tower of God, having Crunchy Roll premium is amongst the most predictive factors whether or not someone is watching Wistoria: Wand and Sword. Based on tracking Wistoria‘s placement in the Crunchy Roll app/website across multiple accounts, I feel confident that this ubiquitous placement within the Crunchy Roll experience is one of the most relevant factors to its distinct success in the U.S. market.

The Rest

©Sunsunsun,Momoco/KADOKAWA/Alya-san Partners

Alya Sometimes Hides Her Feelings in Russian is, somewhat surprisingly, the most popular anime of the season in the U.S. and not far behind in Japan. To say it’s had a bigger response in the States would be technically accurate, but would also expose a core challenge with this method of comparing popularity. It’s the top simulcast of the season in the U.S. and one of the top in Japan. It’d be amiss for me to ignore it from the analysis altogether, but there’s not too much to say about it besides citing it as an additional piece of evidence that anime fans in the U.S. are gravitating more towards the tastes of Japan.

© Anime News Network/White Box Entertainment

My Deer Friend Nokotan‘s near-equal popularity across territories similarly represents a gradual evolution of Western tastes. Series that centrally feature comedy like SPY x FAMILY and Kaguya-sama: Love is War have no trouble becoming some of the most popular anime in the U.S., but pure comedies without an overarching storyline have historically struggled. However, thanks to virality on social platforms during its launch campaign, My Deer Friend Nokotan became a strong performer on both sides of the Pacific. Don’t get me wrong, the total addressable market for a show like Nokotan is still only a fraction of an anime that aligns with American fans’ priors like JUJUTSU KAISEN. Yet so many people were willing to try out this kind of absurdist comedy indicates that U.S. audiences are broadening their anime palettes.

© ???/??????????????

As mentioned earlier, Dungeon People is desperately under-watched in the English-speaking territories. It lays claim to the title of “most disproportionately liked in Japan,” but like most anime with that distinction (think Sound! Euphonium, Uma Musume, SLAM DUNK, i.e. anime I like), it’s quite well-regarded amongst the most enfranchised anime fans in the West. YouTube-based anime critic Tristan Gallant recently cited it as his favorite anime of the season.

My Hero Academia

This chart is focused on anime of the summer season that began in either July or August, so many continuing titles will be absent, as are others that didn’t have enough data for me to feel confident with the results. However, MHA is in an interesting place and worth an aside. My Hero Academia‘s seventh season would be in the top 5 in the U.S. and Japan, but it’s not quite an apples-to-apples comparison with the available data. MHA peaked in popularity for its third and fourth seasons, and while its current season displays a meaningful uptick in interest compared to the two prior, its viewership is not the dominant force it once was.

© ?????????????????????????

For American audiences, a significant element of My Hero Academia‘s impact flagging is related to the dub. For the first few weeks of seasons 2 and 3, Crunchy Roll (then Funimation) would produce true “simuldub” episodes, where the English dub would premiere alongside the subtitled release. Since then, however, the series has had a much more practical two-to-three-week gap. This isn’t an issue for most other shows, as the audience that strongly prefers dubs in the U.S. is typically only 10%-20% of total viewership per piracy data and survey responses. However, the MHA dub is particularly beloved by fans and accounts for nearly half of all viewership by our measures. Once someone begins watching a show in one language, they prefer to keep it consistent.

When the show had a true simuldub, there was more of a culture around watching the show the moment it came out, and it hit a critical mass of the audience engaging with new episodes at the same time. Without that, MHA loses a particularly engaged part of its audience, who now wait to binge-watch the show at the end of each season at a higher rate than the typical simulcast viewer. This essentially splits the audience and diminishes its visibility outside of the audience of already dedicated viewers.

The Conclusion

For the careful observer, there aren’t many massive surprises in this popularity analysis. I’m always relieved when the results come into line with my expectations the more we collect additional data, but I still revel in the occasional surprise. For the summer season, seeing Kimi ni Todoke‘s U.S. audience stay strong 10 years after the series’ previous outing was a delight that I had not anticipated.

I believe this analysis represents a step in the slow convergence of the global anime community’s tastes and preferences. What is Japanese is much less foreign to American viewers than it was for previous generations, and Gen Z’s love of subtitles is a huge boon for the future of anime in this country. A few outliers like Rick and Morty: The Anime or Tower of God may be extreme, but I don’t have reason to believe that they’re representative of larger trends.

I’d love to know what your thoughts are! Please feel free to ask questions in the forums, and I’ll do my best to respond.

Disclaimer: Miles is the CEO of White Box Entertainment LLC, a consulting company with clients that include the publisher and/or distributor of several of the titles discussed in this article, including: My Deer Friend Nokotan, Why Does Nobody Remember Me in This World?, Our Last Crusade or the Rise of a New World Season 2, No Longer Allowed In Another World, Mayonaka Punch, VTuber Legend, Dahlia in Bloom, Days With My Stepsister, [Oshi no Ko] Season 2, and Alya Sometimes Hides Her Feelings in Russian.